|

|||||||

MEDIATION IN CIVIL & COMMERCIAL CASES:options as to processA short survey of other approaches to dispute resolution available in the context of civil and commercial cases, and an introduction to the dispute resolution continuum, a tool to assist in understanding the differences amongst them. contents of this section

|

|

||||||

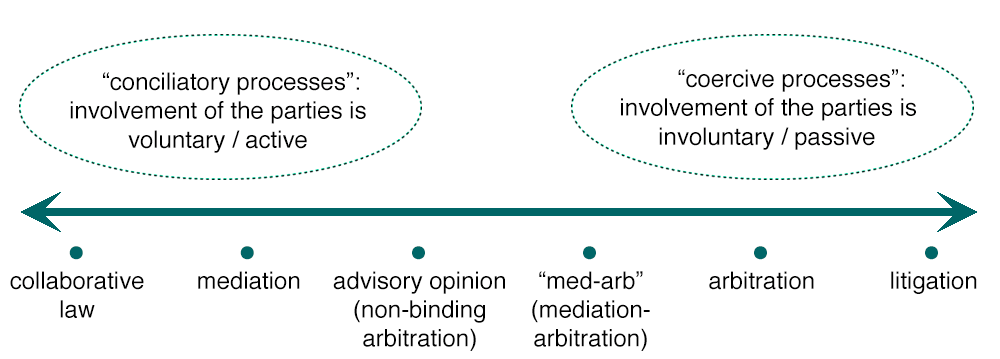

• ADR Continuum & Choice:In this section I am going to work with a continuum - a sort of scale of dispute resolution methods that ranges from voluntary process, in which the active involvement of the parties is central, on one hand, to a process in which the parties may be obliged to participate whether they want to or not, and in which their role is passive, on the other. When I place the various process alternatives on this continuum, the result looks like this:

This is not a judgment on the choices people make as to process. Given their preference, I think most people would opt for the process they believe would be fairest, quickest and cheapest for them, and I think most would probably want some input into the result. But there can be limitations on the ability to choose. For example:

To be clear, the processes at the more informal and conciliatory end of the continuum can only take place through the consent of the parties. If the parties are willing to give some thought to their process, and to collaborate in organizing it, they can create a procedure that reflects their wishes as to involvement, formality and expense. Where the parties cannot agree on such a process, they will end up with one of the more coercive processes at the other end of the continuum - arbitration, or the most extreme form of process, litigation. • mediation:Mediation is an informal settlement process by which the parties try to reach a solution that addresses their various interests and needs. Mediation does not alter the parties' existing rights and responsibilities unless they expressly agree together that they wish to do that. The mediator is a facilitator, only, and does not have the power to decide any issues between the parties. The mediator's role is to assist the parties in negotiating a voluntary settlement on the issues, if that is possible. On the continuum, you will see that mediation lies towards the left end ("conciliatory": voluntary/active). This reflects the fact that the parties have the opportunity to --

A more detailed understanding of mediation can be obtained by reviewing the "terms of mediation" that are accessible by the tab above. • advisory opinion:This is sometimes referred to as "non-binding arbitration", but I think the name "advisory opinion" less confusing. The simplest version of this method is for the parties to agree upon an expert in the field of their dispute, and retain that expert together to give them an opinion as to an appropriate resolution of the case. Another version is where a mediation has been conducted, but settlement cannot be reached. The parties may want help at this point, because their remaining options are arbitration and litigation, both of which are comparatively slow, complex and expensive. In this situation, the parties could agree that the mediator give them his or her opinion as to the merits of the case and suggest solutions that might be appropriate. What is distinctive about this method, is that the parties retain control of their dispute process -

But if the parties do not choose to settle based on the opinion, they may find themselves back in a bargaining process and may find that it is deadlocked, in which event arbitration or litigation may be the only options remaining. • "med-arb" (mediation-arbitration) agreements:In any case in which mediation fails to yield a settlement, parties may decide to go to arbitration, but that is not the situation to which the term "med-arb" generally refers; rather, the term "med-arb" refers to a special kind of agreement that provides from the beginning of their relationship that the parties must go to arbitration if mediation of any dispute that arises between them should fail. It is a "hybrid" agreement -- it provides for both mediation and arbitration. Under a med-arb agreement, the process starts with mediation. The mediation part of a med-arb procedure is conducted in the same way as any other mediation, and has the same "voluntary" character. However, if the case is not resolved through mediation, and moves forward into the arbitration stage provided in the med-arb agreement, the "voluntary" character of the process changes. That is because, once it has come into play, arbitration in the context of a med-arb agreement is governed by the same rules as any other arbitration. Thus, if settlement is not reached at mediation, the med-arb process shifts from mediation to arbitration, the more coercive character of arbitration comes into play, and the person appointed as arbitrator will decide the case. (I am referring to voluntariness and coercion as those terms are used on the continuum set out above, and to the fact that arbitration falls at the involuntary/passive end of the range). A med-arb agreement is often used in anticipation of an impasse in bargaining, as a way to break such an impasse if it occurs. It operates that way because, by comparison to mediation, arbitration can be complicated, expensive and slow. The knowledge that they will end up in arbitration if they are unable to settle at mediation tends to spur people forward in their negotiations while mediating. This coercive aspect of med-arb may not be objectionable if the parties are in agreement from the outset that they want it, but a word of warning: many commercial agreements like vehicle leases provide for med-arb in the "small print" of their contracts, so you could find yourself inadvertently agreeing to such a process without addressing your mind to it — and even if you were to recognize that the agreement included such a clause, you might find that you were unable to negotiate its removal .... I encourage the reader to look at the material on arbitration set out below for further information about the arbitral part of med-arb. • summary and "shotgun" methods:These are also methods of breaking impasse in negotiations. The neutral person referred to here is often a mediator who has been working with the parties, though there is no requirement that this be so. In the most summary form, the process may be as simple as the parties authorizing the neutral to flip a coin, the result to determine which of the positions of the parties is to prevail. In this situation, the parties have delegated all decision-making power completely, and the result is random. An alternative is for the parties to submit their best offers to the neutral, authorizing the neutral to consider those offers and then make a decision that (s)he thinks best. While the parties had the opportunity to choose their decision-maker, this is a complete delegation of the power to make the decision itself - it is an arbitration. There is a variation of that last method that retains more control for the parties: in this version, they submit their best offers to the neutral, authorizing the neutral to decide between the offers. The neutral is sometimes referred to as "the selector". While the parties have delegated their power to make the decision, they have limited the neutral's role so that (s)he has no discretion, and can do no more than pick between the 2 choices. This dynamic tends to spur the parties to make their very best offers. While these last two methods are technically "arbitration", because the third-party neutral is empowered to make a decision for the parties, they are not full arbitral processes that weigh evidence and consider law. In fact, these methods can be quite haphazard; however, notwithstanding the risks attendant on such random process, the parties may prefer a summary or shotgun method to a more elaborate process in order to save time and money. • arbitration:In arbitration, the parties sign away the right to devise their own solution to their problem: if they cannot settle, the person appointed as their arbitrator will make the decision for them. The arbitrator will also decide questions of procedure and evidence during the course of the arbitration, if the parties are unable to do so. These characteristics are essentially coercive, by which I mean the decisions themselves do not require the parties' consent. Once the arbitrator is appointed, the right to make those decisions flows automatically from the appointment. This is why arbitration is placed towards the involuntary end of the continuum. This coercive character extends to the the courts' treatment of arbitration. Generally speaking, if a party tries to escape arbitration to take the dispute to the courts, (s)he is likely to find that the Court will refuse to entertain the case and will send it back to the arbitration that was agreed upon. Similarly, where necessary, the courts will lend their authority to make the arbitration work by making such orders as -

But arbitration has advantages, too. Some examples —

All of which is to say that, if the parties insist upon digging in and dragging their feet, there is no magic in arbitration: in such circumstances it can take just as long as litigation, and can be just as expensive, or more so because, in arbitration, the parties are paying for their "judge" (ie, the arbitrator) as well as counsel. • collaborative law:For the parties, collaborative law is the most voluntary and active dispute resolution method available -- it was created in the context of family disputes to put the clients at the centre of the process, rather than on the side-lines as their lawyers conduct the case. Collaborative cases are conducted through a series of 4-way meetings, which are meetings of the two lawyers and the two parties, face-to-face, at the same table. The parties act as their own advocates at this table. In collaborative law, the principal task of the lawyers is to teach and coach their clients because, at the meeting table, discussions and negotiations are conducted by the parties rather than the lawyers. The lawyers are also disengaged from the case by contract: they are required to agree at the beginning of the process that, if the case fails to settle, they cannot act as counsel in any subsequent litigation. This is done to remove any temptation presented by litigation fees so it cannot distort or complicate the collaborative process. In one variation of collaborative practice, the 4-way meetings are expanded to a fifth participant - a mediator. If discussions have been raw, or if discussions simply need to be more organized and focused, a mediator is trained to have insight into the dynamics of the session and can take steps to identify and correct impediments to the process. Collaborative law has yet to take hold in Ontario in matters other than family law, but I think collaborative law methods would be useful in many civil and commercial cases, especially estate disputes and disputes within closely-held businesses, partnerships and corporations, where relationships are entangled in the problem, and relationships are often part of the solution. I hope to see this method gain a foothold in civil and commercial practice as the public and the bar become more knowledgeable and creative in the use of ADR processes. |

|||||||

Copyright © 2011-2025 • Jane Demaray, All rights reserved.